Have you ever noticed that it seems you always turn your USB the wrong way round when you go to plug it in?

So you have to flip it over, with the overly inquisitive lady who’s a fixture of this drugstore eyeing you like a hawk and then you can finally print those photos of your dog in a lil cowboy hat.

Do you really always have the USB turned the wrong way around? Or is it just that things going wrong tends to stick in our memories better than things going right?

This is an example of sample bias.

Defining Sample Bias

There are many terms in this realm with overlapping meanings: sample bias, sampling bias, implicit bias. The essence of what I’m trying to say is that these terms point us to blindspots and the attendant difficulty in understanding the world. You might be interested to see this conundrum as it relates to sample bias in a census.

We’ve got one coming up in the US this year, you know.

Tempering our intuition with testing can combat sample bias. A common story that we tell ourselves about “experts” is that they gradually and imperceptibly develop a sixth sense about their field from years of lived experience. Now, this is true in a way, but the process isn’t so mysterious or impenetrable. Building expertise is often just running numerous experiments and changing your hypotheses as you get new data and test again.

And again. And again.

Sample bias leads to poor analysis and decision-making. It blinds us to the world that is right in front of us: we approach a situation without realizing the assumptions we bring to it.

Overcoming Sample Bias: Envisioning What’s Been Left Out

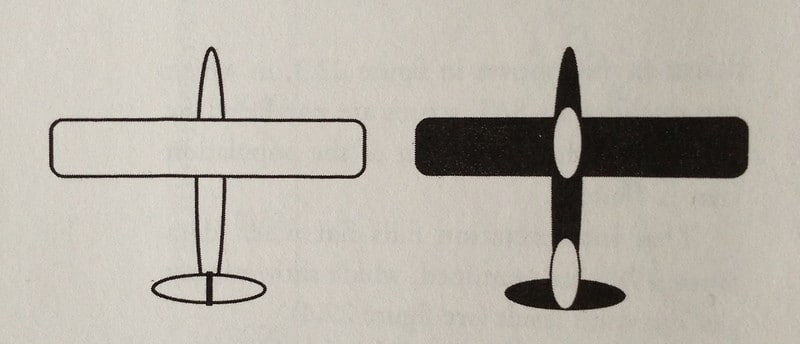

During World War II, the military tried to assess how to better armor its aircraft. Hundreds of planes coming back from the front were examined for damage, bullet holes mainly. This image of the plane on the right represents the data. Black areas signify more damage; white, less damage.

Where would you have recommended reinforcing the planes?

Pencils down!

Mathemagician to the Rescue

Luckily for the Allies, Abraham Wald was on the case. Wald was a mathematician who took on this very question for the US government via his post at Columbia University. (I learned about this nugget of history in WORK RULES!, Laszlo Bock’s book about why Google is consistently rated a great place to work.)

What Wald advised might seem counterintuitive: that the cockpit and tail should be reinforced. He had the clarity to realize that the data wasn’t presenting the whole picture. It only represented the planes that made it back. Those that were shot down were not being considered.

The prevalence of bullet holes in the wings, nose, and center section of the fuselage meant that those parts of the aircraft were actually more durable and less in need of protection. It was the cockpit and tail—generally unscathed on the returning planes—that were essential to protect. A single bullet hole in those vulnerable areas likely spelled disaster.

Sample Bias: A PPC Example

Let me bring sample bias a little closer to home, to us as marketers.

What I Assumed

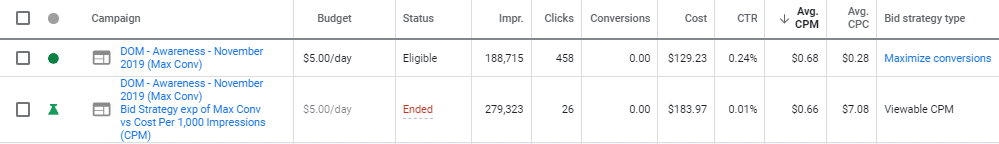

I ran an experiment on the bidding strategy type for a client. It was a display campaign with the ultimate goal of driving brand awareness. The client had the campaign set to the maximize conversions bid strategy; I hypothesized that a viewable cost-per-thousand impressions bid strategy would drive more impressions for a lower cost. In fact, I didn’t just hypothesize it, I guaranteed it (in my head at least).

Why did I believe this so firmly? First of all, because that’s exactly how Google explains Viewable CPM—as an algorithm aimed at putting ads in front of people for less spend. Secondly, because that’s how my teammates expected the experiment would go as well.

Here’s what happened.

What I Actually Saw

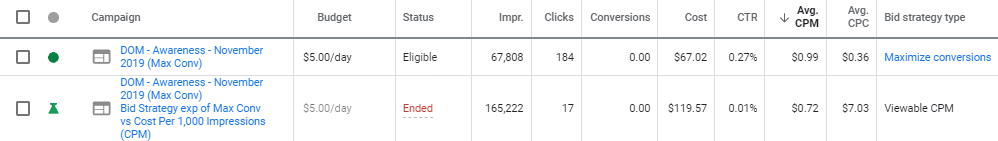

1-week performance

I felt pretty good after the first week. The Viewable CPM strategy had gotten more than double the impressions of Max Conv.

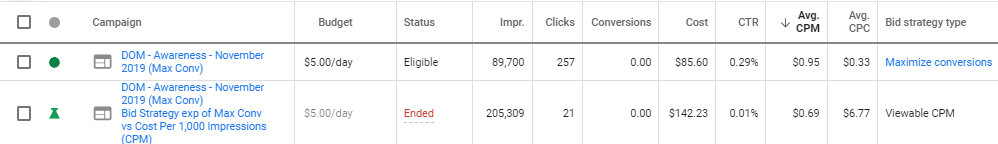

2-week performance

Boy, about then I thought I was hot stuff. More than a quarter cheaper for each thousand impressions.

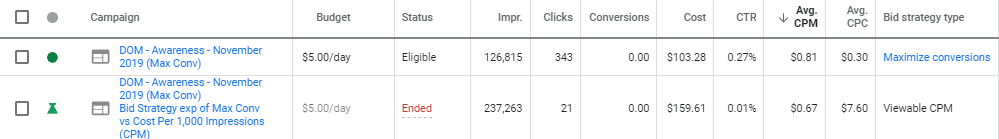

3-week performance

After another week, it was more of the same. I was going Mach 5.

4-week performance

The full month’s story was different. The average CPM ended almost exactly the same for each bid strategy, and Max Conv. got more than 17x the clicks in those four weeks.

I reviewed these stats with the client, and we decided to close out the experiment, returning the full budget to the Max Conv strategy.

I had to doff my cap to the wisdom of testing.

If I’d just gone with what I assumed to be true, I would have missed out on the excellent performance of Maximize Conversions bidding strategy in this case.

Sample Bias and Self-Perception

Correcting for bias in our thinking isn’t only good for PPC campaigns. It’s good for us as people.

Oh, no! FOMO

Fear of missing out—FOMO, as the kids call it—is intensified by the way we interact with social media. FOMO is that vague sense that everyone else is always doing something more exciting than we are.

Facebook and Instagram are pervaded by images of people indulging at fancy restaurants, hiking in perfectly appointed outfits, dancing the night away, starting new jobs, showing off new cars, and displaying especially good hair days.

Sometimes we take these images as the whole story. We implicitly assume that these photos are representative of the lives of those therein.

When you’ve gotten home late from work on a Friday night and pull out your phone, it can seem like everyone else is out having a great time, while you’re the lame one without the right relationship, without the right friends, without the right self.

The problem is we aren’t seeing the whole picture. FOMO is a kind of sample bias.

People usually use social media to share peak events. We don’t typically present others with:

- time spent waiting in the dentist’s office

- getting a flat tire

- anxiety about getting older

or the

- pleasant but ordinary half-hour spent reading before work

- our mother’s cancer diagnosis

- waking up and our back not hurting as much as yesterday

- having Cheerios just when you had a taste for them.

Correcting for Sample Bias in our Lives

When you are already feeling a bit down and turn to social media in your default mode of thinking, you can wind up making things worse. There is an opportunity in such moments to adjust your thoughts: to consider that sample bias may be at play. You are not getting the whole picture. And this can be consoling.

You can come to see the photos of people showing off a new car or being in an exotic locale as a respite for them amidst the misfortunes of life. You can realize that that person in the pixels is probably just as worried about missing out as you are. So why not bask in their moment in the sun, even digitally, from afar.

Keep Alert for Sample Bias and Things Will Be Better

We’re human. We bring assumptions to the table that we don’t realize. We start from a biased framework and get skewed results.

We’re human. We learn from our mistakes—and the keen-sightedness of others (my thanks to Mr. Wald). We check ourselves going forward for the many species of bias.

Ferreting Out Bias in Marketing and Life

- Are you considering the whole scope of the data? Or just a subset?

- Why is your direct traffic in Google Analytics so high?

- Are you invested in the outcome of a test going a certain way?

- Are you accurately tracking users across subdomains?

- Are you using tests to balance your gut feelings?

- Does alt text still matter?

- Are emotions pushing you to a negative conclusion that’s unwarranted?

Happy hunting for those hidden assumptions and unrepresented data! Check out how we’ve seen things that others missed for our clients.